I asked if I could take her picture. It was the polite thing to do in an area that rarely sees cameras. Many villagers believe cameras steal their soul so to shoot without warning could be potentially devastating. But, she agreed. Her large baby was wrapped in cloth across her chest and she smiled, not quite focusing on the lens. I passed her the camera and she took it, staring for a while before laughing modestly. “Would you like to take a photo of me,” I asked, gesturing to the camera and my smiling face. It took a couple of tries but we finally got one out. Yet, the idea was obviously foreign. I was barely in the frame.

A group of boys gathered nearby carving wooden tops on an upturned stump. They were competing for the longest spin, tossing the top from a rolled-up rope onto a flat, dirt patch. The ones who wore clothes had worn-out, holey shorts and t-shirts of 90’s Thai pop bands – obvious hand-me-downs. Others wore no clothes at all and held chickens like pet cats, watching the spinning tops as I’d watch TV.

There was a school in the distant field but none of the boys were there. School only happened when a teacher came to town and this only happened twice a week. It was, after all, a remote village in a section of Laos where no roads go.

The closest dirt road crossed the Nam Ou about one hour down river and the Nam Ou was a winding ten kilometers back through the valley of dusty, dry-season rice paddies. To get to that road – the one ten kilometers back and one hour down river – a small sawngthaew (literally “two rows” of wooden benches in a converted pickup truck) hauled me amid mud-cracked streets and paved bridges with a collection of villagers, their kids, and their chickens. The boat ride from the bridge at Nong Khiaw to the dock one hour up-river at Muang Ngoi Neua brought more inquisitors who, unaccustomed to Western ideas of spatial awareness, draped over my legs fascinated by every move. As I docked at Muang Ngoi Neua and trekked into the river-carved valley, I could see the tourist trail evaporating behind me. This was Asia of my wildest dreams; the so called “original Asia,” and I came here on a mission.

The village men had gathered with a long bamboo pole to pry coconuts from the towering palms. Every few minutes, two or three fell like boulders onto the mud-packed ground, barely missing the thatched, stilt houses. The morning valley fog morphed into beaming rays of sunshine which, bisected by the spiny palms, left zebra-print shadows – bull’s-eyes for the coconuts. As the ground shook under the aerial assault of furry, brown fruit, the kids raced to retrieve.

A small bamboo dam collected enough energy for two or three hours of light each night. That, and an ancient satellite dish, were the only signs of modernity.

Sharp karst mountains, cloaked in a bushy coat, towered above this small village and the winding river, a tributary of the Nam Ou, provided its lifeline. Where the forested hills met the valley floor, terraced rice paddies blanketed the land. Water buffalos, like gargoyles on a cathedral, guarded this flat expanse of pictorial, rural Asia. As I glanced at the children’s book in my hand and the fields in the distance, I saw sixteen-year-old Xengxong’s patchy drawing come to life.

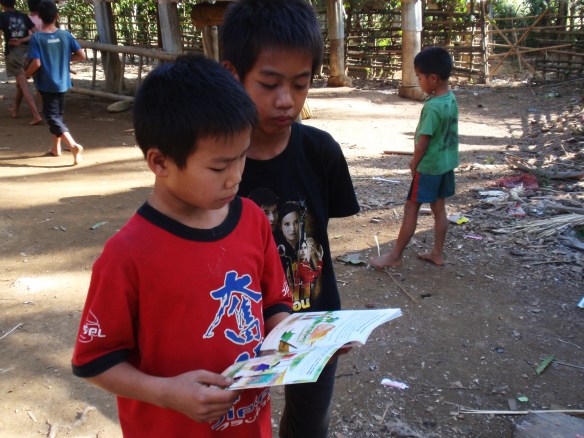

I wandered to this isolated village with three friends and a handful of books from Big Brother Mouse. Our goal was simple: to hand out Lao-language books and read with the kids. The majority of children in Laos do not own a single book. Because education is a ticket out of poverty, these books are an important step towards a brighter future.

There was only a sprinkling of Lao-language books for adolescents before Big Brother Mouse arrived on the scene in 2006. Organized by a retired American publisher and a team of Laotian college students, BBM is not an NGO – it’s a not-for-profit, Lao-owned project with Lao staff. In addition to producing books, they host rural “book parties” and publish books by the country’s up-and-coming writers. I purchased Lao Proverbs: The Wisdom of our Ancestors directly from one of the proud authors at BBM’s Luang Prabong office. In Lao and English, the book was written and illustrated by young people at the Children’s Cultural Center and the Orphanage School of Luang Prabong.

It was so obvious that he wanted my book, but he didn’t beg. Standing in his red, Chinese t-shirt, biting his thumb, he ogled my modest offering.

I remember as a kid when my mom gave me a book instead of a toy I would sort of sigh, mildly uninterested. But, for him, this gift was better than any toy he’d fashioned out of wood. It was better than the game of tops. All of the kids stopped and gathered around to view the new book. Naively, I wasn’t sure if they could even read in Lao (they spoke an ethnic dialect), but slowly they pieced together the words. We distributed the stories to several other children who huddled with their parents and grandparents reading the short parables. Initially worried how we would be received, our visit and our small gifts consumed the entire village. Elders smiled, thanking us, and we were invited to sit and eat with the village’s only English speaker, Mr Bo.

Our perpetually laughing host recently opened a homestay in hopes of attracting more visitors to his village. As it turns out, it was his sign that led us through the labyrinth of rice fields in this direction. Mr. Bo’s wife was out fishing so he lamented that he would have to cook the meal and it wouldn’t be as good. He was right, but we didn’t mind. His one joke repeated throughout the meal but we laughed every time. Wide-eyed kids gathered to watch us eat, say, “hello,” count, “one, two, sreee, four, five,” and repeatedly wave and giggle. In remote areas like this, you grew accustomed to a celebrity status.

Our visit was short (just a few hours), but the impact was felt. It was days before Christmas and with no family or co-workers to appease, no dirty Santa parties or stockings to stuff, I chose to visit a couple of strangers instead. I only spent a few dollars but sometimes that’s all it takes. Volunteering is not as daunting as it sounds.

As we returned to the sun-drenched valley, we passed Mrs. Bo marching home with a gaggle of wrinkly, hunchbacked ladies. “Where are you going? Did you eat yet?” she asked, holding a bucket of flopping fish. About an hour too soon it seemed.

She bid us farewell and went off to cook her fish. The kids had returned to their game of tops and the adults ambled around chasing chickens, feeding babies, and preparing the evening’s meal.

One of the proverbs in the book I’d left read, “You know, you teach. You don’t know, you learn.” I read it aloud thinking to myself, “I am the teacher.” Yet, when I left, I wasn’t so sure. To quote another Lao proverb, “Though he who walks behind an elephant may feel very confident, he is likely to get splattered with dung.”

——————————————

Want to sponsor a book? Visit BBM’s website HERE